Created by

Nyssa Chow

.00

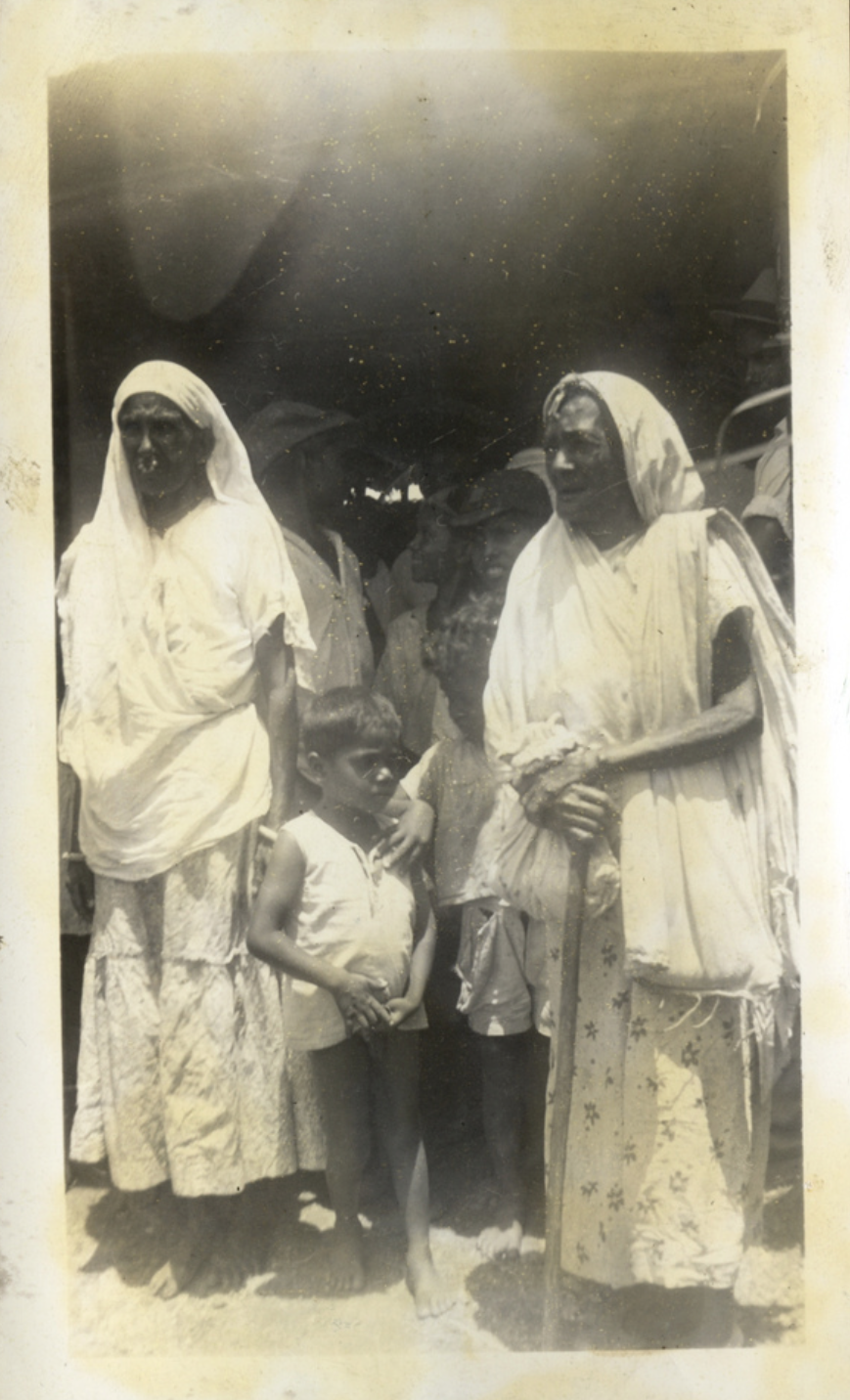

Look at these women.

There is a story here. This is my Great Aunt Silla, my Great-Grandmother Sasa, and my Grandmother Cecelia. There is an assertion of grace in this image. It was taken during a time when scientists were speculating that these women had more in common with an ape, than with a human being. There is a message about a way of being encoded in this photograph. I can’t say for sure, but I suspect it has something to do with the fact that they are dressed in white, even though the roads would have been muddy and unpaved from here to anywhere they were expected to go. I suspect it has something to do with my grandmother's unruly, natural hair stretched back into that neat bun. The way British women wore their hair. Or something to do with my grandmother’s love for the Queen of England, though she would not have been welcome on the grounds of the Country Club, except as a maid.

The following is the life story of my Great Aunt Silla Rosales. It traces her friendship with my Grandmother Cecelia. Both are daughters, wives, mothers and grandmothers. It spans five generations, including my own.

.01

It was near the end of our conversation that day, and Silla had shifted the focus of the story onto me. My Grandmother Cecelia had worried about me back then, she’d said. When I was a child, people always said I looked like my grandmother.

There were two times during any day when I, as a little girl, would sit at my grandmother’s knees. Once a night when we would pray, and once an afternoon when she would comb my hair. At night, just before bed, she would call me into her room, sit me next to her on the edge of the leatherette armchair, and teach me how to pray from her book. It was in large print, its cover wrapped neatly with white paper, the way children’s government textbooks were covered to protect them from carelessness and damage.

“The Salve Regina,” she would say, and we would read aloud.

Hail Holy Queen,

Mother of Mercy,

Hail our life, our sweetness and our hope.

To thee do we cry, poor banished children of Eve.

To thee do we send up our sighs,

Mourning and weeping in this valley of tears.

Turn then most gracious advocate,

thine eyes of mercy towards us

And after this, our exile, show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb…

I know this prayer by heart. It was my grandmother’s favorite. I only ever hear it in our synchronized voices in my head. We, the banished children of Eve.

During the day, usually at the most inconvenient time for children, prime playing time when my cousins might be outside fighting imaginary wars with stick swords or tumbling out of trees, I would be sat between my grandmother’s knees. It would take at least at hour to comb my hair — it was thick and unyielding, like her own hair. Lift up your head. Lift up your head. Lift lift lift up. Stop moving. Stop wriggling. Ow ow ow! Lift lift up. Up. Stop pulling.

I was the only one not playing outside, because I was the only one.

"This hard head yuh get from yuh fadda,” she’d said once, “Lift- Lift- Lift up your head!”

My hair was not at all like my mother’s good hair. My Grandmother had married a Chinese man, and brought into this world eight light-skinned, good-haired babies. And they went on to have good-haired babies. And then there was me.

“I told your mother not to marry a black man,” she said once. I’d never met this black man, he’d run off early. I’ve often thought this hair might be the only thing I'd gotten from him. My grandmother’s black father had run off early too. Two banished children of Eve, good brown, but bad hair. But I hadn't perceived this connection between us when I was still young, and her knees were still squeezing me on both sides to hold me steady. Then, I’d had the sinking feeling that I was loved in spite of the fact that I had been born a disappointment from the top down. It wasn’t until I heard their story, the story of my Great Aunt Silla and my Grandmother Cecelia, that I really understood that these moments were never about me at all. She was angry at my mother — my mother had failed to rescue me from blackness, it had been her duty to do that, and she had failed me.

People always said I looked like my grandmother, and I see now, how that must have grieved her.

I didn’t know it then, but these moments with my grandmother had a history. And like all histories, it is a nested story: the story of Silla and Cecelia, nested in the larger story of an island colony, all within the global story of empire, and the history of race itself. As I listened, I realized that I was hearing a history of what it might have been like to live in a body that looked like mine in a particular time and place - Trinidad in the 1930s. Their histories were my history. Their history is also, the history of my skin.

This story begins in Poole, Trinidad. The estate village where Silla grew up.

.02

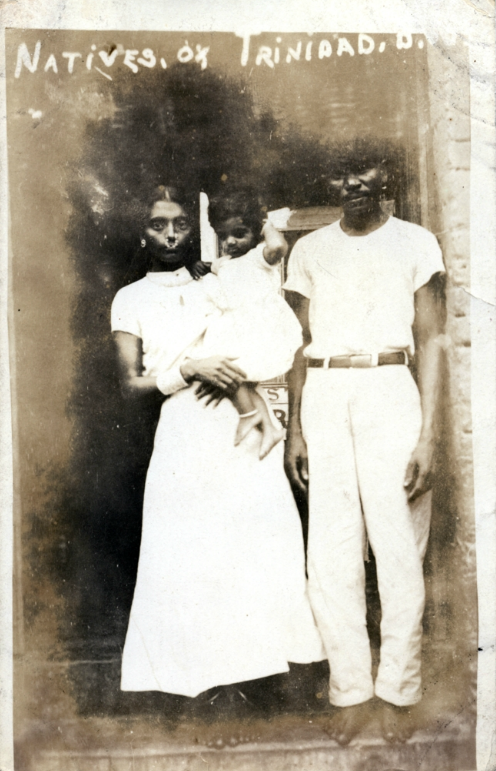

Two brown girls from Poole. One without a father, and one without a mother. Cecelia’s father had run off to Canada years ago, and Silla’s mother had died. They were only five years apart, and yet Cecelia was Silla’s aunt. They were aunt and niece, a relation made possible by the arithmetic of hardship whereby a girl could be married with two children by the age of eighteen.

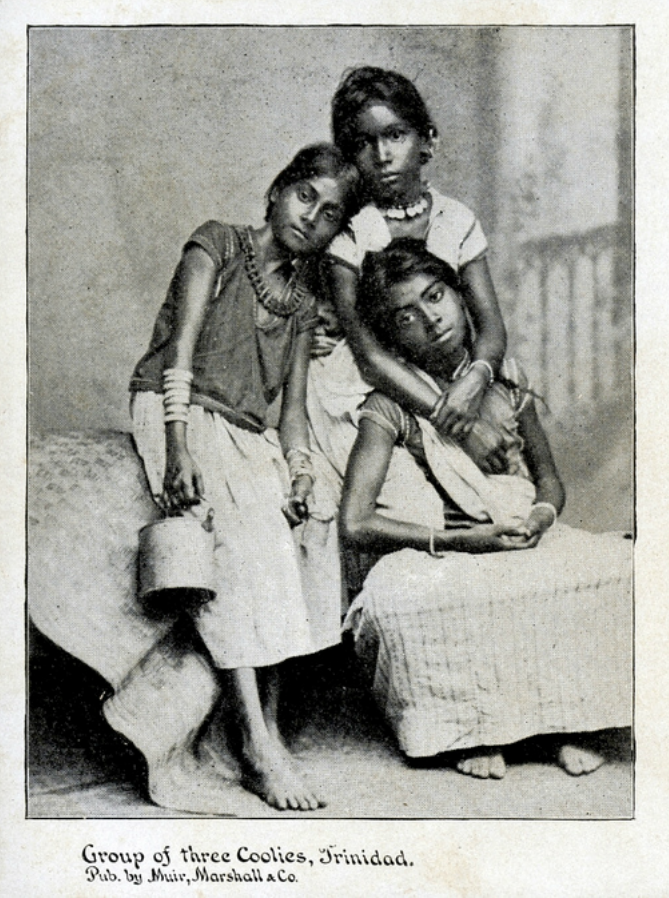

And it was the arithmetic of colonialism, and its organizing principles, that made it so a brown woman’s skin color was her wealth. Trinidad has as rigorous a taxonomy of skin tones, as an Alaskan might have classifications for snow. There was brown, high-brown, yellow, high-yellow, black, congo-black, dougla, whitey, spanishy, fairish, red, sugarhead, chiney, happa, half-chiney, chindian, indian, black-indian, veni, white, trini-white, payol, arawak, creole, syrian, and so on.

Silla was ‘good-brown’, and so was Cecelia. Silla knew what this meant even as a child, and her community knew it. She possessed a path out of Poole that her darker skinned half-sister Merle did not. Silla could marry up, and ascend to a different class, pulling her family up with her. And this knowing afforded her aspirations, ambitions. Even as a child, she anticipated what so often goes unacknowledged - that the tangible fact of her skin tone would be implicated in every choice she would make, and in every choice she would have the opportunity to make.

“Rural Trinidad. 1930s.”

.03

CECELIA

By the day of Cecelia’s mother’s wedding, a few things had already been decided in the young girls’ lives - They were poor, in a colony, on an island, whose boundaries traced more than maritime borders. They traced the perimeters of limitation within which they could make their possible futures. Cecelia’s mother ‘Sasa’, this house, and even this marriage were contained within its limits. This marriage was necessary. A brown woman, without an education, already thrice a mother, already once married, could only survive without a man, but never thrive. A man meant income, it meant a house.

The wedding party was still in the house. Cecelia’s mother had just been married. The two girls were playing, happy for the chance to be together, when Mr Stafford, the mother’s new husband, must have heard their noise and had come in charging,

‘Stop that noise!’ and then he’d slapped Cecelia.

“That was the day I knew my life had truly changed,” she would say later. She was nine years old. They would leave her hometown of Poole, and move to Rio Claro with the new husband and his daughter, and Silla would stay behind.

Years later Silla would learn how hard life had become for Cecelia then. How he had been cruel, and had never spared her. That her mother and the new husband had fought in the streets, and that this had embarrassed her. How he had gone to the local Spanish priest, one of the last of the original missionaries, and had accused her at nine years old of sleeping with men, setting the neighborhood talking behind her back.

"Your stepfather gone to see the priest,” they'd said, and she had trembled.

But the Spanish priest had summoned Cecelia, and said conspiratorially in the confidence of the confessional,

“I don’t believe one thing your stepfather said. You’re a good girl. Go and live with your grandmother.” And Cecelia had never felt more relieved in her life.

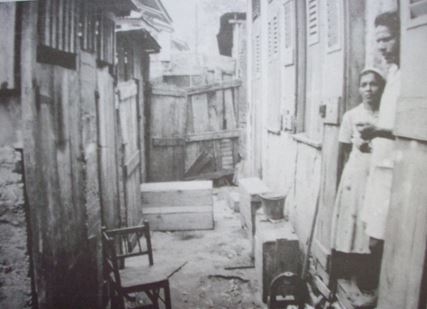

“Barrack Yards. 1920s”

Cecelia had left her mother, and had gone to live with her grandmother in the barrack yards — this was housing for people who worked on the plantations. It was the 1920s. One generation away from slavery. Trinidad was a British colony under the crown of King George V. No one on the island had lineage the predated Columbus - everyone here had been brought, bought, had been took, had been arrived — save for the scattering of Amerindians who were steadily losing their language to the inevitable. It was one of the most ethnically diverse colonies in the empire, and Silla and Cecelia found themselves brown-skinned, in a racial hierarchy that ranged from the white British and Portuguese colonists, to Christian Arab merchants, the Chinese who'd graduated from indenture to commerce, the Indians still newly emerging from indenture’s purgatory, and emancipated black and mixed race descendants of slaves. The poor were all poor together, often living in the same neighborhood and even marrying. But the rich and white lived in a world apart. In Poole, one might live out an entire life without ever speaking to a white man. It was rural, split into plantations, and subdivided into lots mortgaged to black and brown people of little means.

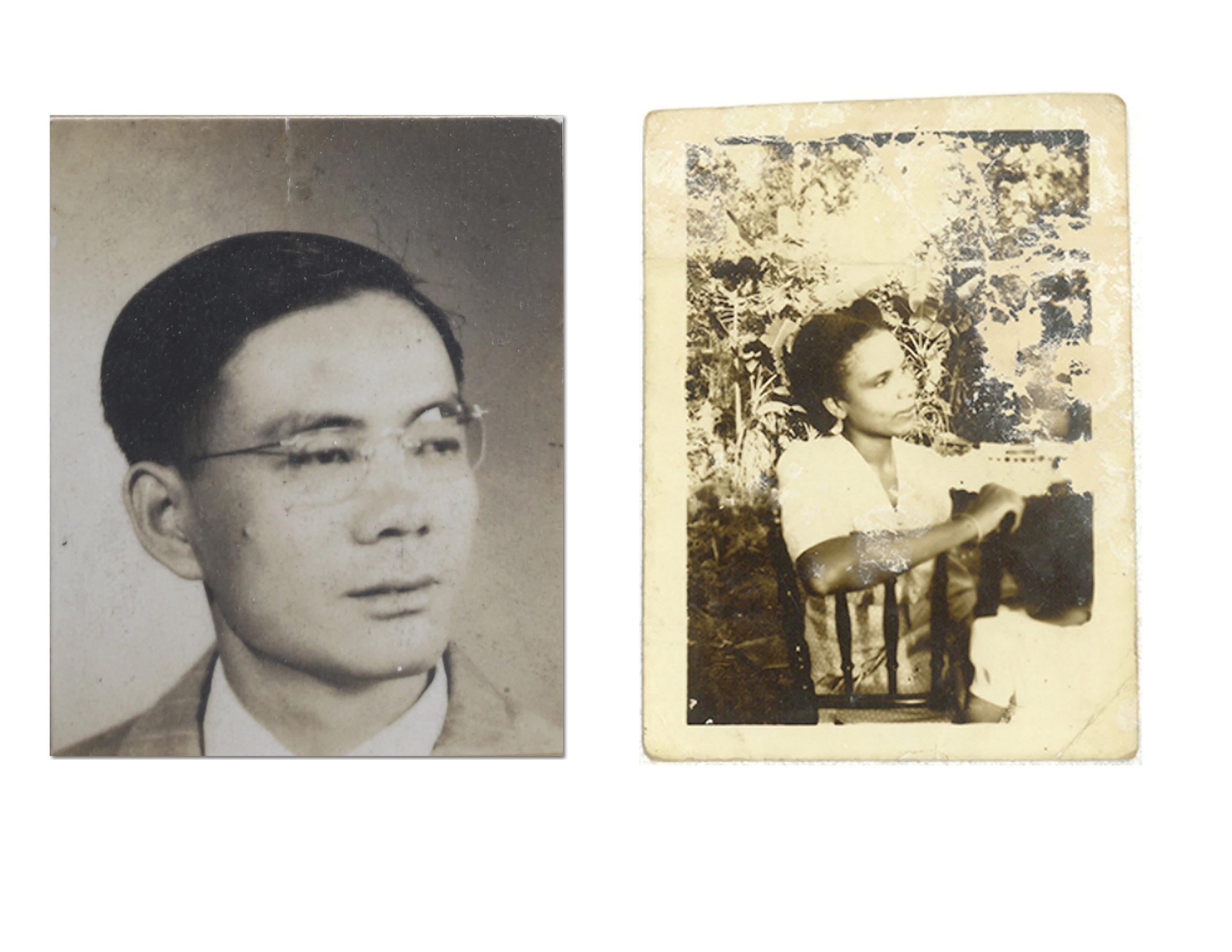

“Sasa with grandchild. Born 1899.”

If a Christian hoped to read the Bible, it was imperative that they learn to read and write. The Roman Catholic and Anglican schools at the time, were doing diligent work. Many brown and black people, even Hindus who'd strategically converted to Christianity, had the church to thank for their literacy. But Cecelia had been bestowed an additional grace, a saving grace who’s reverberations would be felt through successive generations of our family, not yet born — This was Mr. Mitchell.

The angel of my life was Mr. Mitchell. He had come to Rio Claro when I was in my standard four class. And at that time I loved nothing more than learning, the school activities the guides, Legion of Mary, choir. And because Mr. Mitchell was my guide and my mentor, I progressed well. He was kind to me... he knew the circumstances of my life, and he would supply the money for books, uniforms, outings… actually it was this same help that got me into trouble with my stepfather. I suppose, seeing me with all I needed, he presumed that I was taking man. The same stories he took to the priest, he took to Mr. Mitchell - but of course, Mr. Mitchell knew better, because, he was the good angel of my life, at that time.

-Cecelia

If being rescued from her Stepfather by a priest had made her devoutly Catholic all her life, then being rescued by Mr. Mitchell from a life without poetry, without aspiration or agency, had made her a devout of education.

“Cecelia. Born 1921.”

When she’d entered her teenage years, Mr Mitchell would offer her a post in the school, giving her this chance, because she was bright, eager, and he knew the needs of her home. It is difficult to overstate how few of the girls born to barack yards would have gotten an opportunity like this. Teaching was one of the few self-determined ways poor women could steal into the middle class. Only the middle class or rich, could afford to send their children to high school, and the primary schools for the poor were remarkably unproductive. Even where they were functional, students attended sporadically, moving in and out of primary education with the phases of the harvest. In the French Creole drawing rooms of the planter class, vigilant conversation warned of the dangers of bankrupting the supply the rural workers with too much education. For their own good, the conversation reasoned, education should be vocational. It was best not to encourage educational ambition, which only seeded a disinclination to work the land, and left them precariously straining beyond their station in life. The government had divested from public education, leaving the religious schools to serve where they could.

As a teacher, Cecelia made four dollars a month, and she was happy to be employed. She also got ten dollars a month in a job on the estate, keeping financial accounts for the estate boss whom she referred to as ‘The White Man’. She’d been taking the necessary exams to become a teacher. Back then, if a woman wanted to be a teacher, then she could not get married, that was the law. Cecelia was certainly not short on suitors, she had many — she was ‘good brown’, and so she was beautiful. But teachers were to remain unmarried, and my Grandmother Cecelia wanted to be a teacher.

Life, it turns out, had its own plans.

James would walk me home with his bicycle. He’d come from China when he was about twelve years old, and I'd been teaching him how to read and write in english. His mother had died, and when his stepmother started to mistreat him, and beat him, he'd run away from home. He left China with an uncle who'd been to Trinidad before… I remember the first time he came to the house I was so embarrassed. It had rained that day and the ground was muddy, and we had to walk across a plank of wood to get to the door. Mud had splashed on him. I was embarrassed. He was interested in me, as were a lot of other boys. Almost from the start, he asked me to marry him. But I wanted to be a teacher… so I was not going to marry.

- Cecelia

There is a story about a different young man. Cecelia had been interested in him, and he had come calling at her mother’s house. He was black. Sasa had shot out of the house, laid down in the middle of the street, and had threatened to let herself be run over by an ox cart if Cecelia were to try to marry a black man.

The thing you must understand is this: Sasa’s belief that a black husband would bring no material advantage was not subjective bias alone. It was pragmatism. A black man could not get a loan. Without a loan a black man could not get a house. Without a house a black man could not put a wife and children under a roof, under a stable future. To marry a black man, when your skin afforded you the option to do otherwise, would have been to betray the future of your family. You carried a debt. A debt to the woman who, all those generations ago, might have been taken, before the age of consent, by an estate man. Whose brand of lightness her bastard child would have worn on their face, and branded onto the face of the child that would come next, and the child that would come next after that. This child was you. You owed a debt to her undemocratic sacrifice, and its consequence rendered precious by time, history and circumstance.

This skin is your wealth. It is inheritance. You will not squander it.

This was the story of Cecelia’s skin, of Silla’s as well, and of my own.

Cecelia’s mother Sasa was thirteen when she had her first child by the Estate Man, the overseer, the ‘Cocoa Payol’ who owned every earthly thing she would have seen, eaten, slept in, or come upon at that time in her life, including her bible, and the road that led to the church. She was fifteen when she had his second child. He would have been a landowner of Spanish or Venezuelan background — ‘high brown’. To leave for another estate would have been to slip from one hand into another. There were no unsimilar options. Black and brown people had been emancipated some eighty years ago, but they were still owned.

Sasa’s mother, ‘Mama’, had straight hair, and she was" high brown’. I'd once asked where Mama’s straight hair came from, and my Grandmother Cecelia had simply said,

“Plantation business.”

No record exists of any further explanation, it is a silence in history. She too, had her first child at thirteen.

“Local San Fernando dignitaries and businessmen. 1903.”

“1906”

Unlike a black or Indian man at this time, a Chinese man could get a loan, even one as young as James was at the time, still only recently a boy at seventeen years old. And with access to the nepotism of the Chinese business associations, he could start a business. Black and brown people were locked out of commercial enterprise. The children from such a marriage would be automatically born into a different social class than their mother — lighter-skinned and better haired. Even though Cecelia had more education than he did at the time, as James would have left school at twelve years old, it was no matter. Those doors were closed to her without him.

Mr. Mitchell, her mentor, had been stridently against her marrying. She would be throwing away her future, he’d said. He pleaded with her not to do it, and Cecelia had labored over the decision. She’d prayed over it. She’d had even gone to see ‘The White Man’, the estate boss she’d worked for, and he’d advised that she should do what was right by her family. James had already asked for her hand twice, and had said he would not ask again. Time was running out.

It was July, at the end of one of their reading lessons. She had taken out a piece of paper, and on it, she’d written:

‘MRS. CECELIA CHOW’

And then she’d said, “You know what, that’s not sounding so bad you know…”

She was married on September 3rd, 1939 . And shortly after, she would be a mother. She was eighteen.

“So you see?” she’d said to me after telling the story of how they met, “All you young people only think about love, love, falling in love. Love is everything. But for me, love came later. We grew to love.”

“James and Cecelia.”

On the day of the wedding, Mr. Mitchell was still angry over her decision, so angry in fact that he and his wife had refused to come to the church.

I went around to all my family and friends to get pledges for what they could give me. One could give me chicken, another vegetables, another rice. On the wedding day, all of them honored their promises, and I had a wonderful wedding. Silla, my niece was most present, coming to the wedding in a big car.

It was the day that England declared war on Germany.

- Cecelia

James spoke english, but not very much yet. My grandmother spoke no cantonese. She couldn’t cook Chinese food, and anyway she didn’t like it very much then. She would cut up the vegetables and James would cook the Chinese meal. To her neighbors’ eyes, she had secured a prize, and some were envious. They wondered if she thought she was better than them now, and sometimes she would catch their evil eye. But the Chinese people saw her differently. There was no such thing as ‘good-brown’, and absent this nuance, she was just black. She would struggle with their scorn, and demoralizations. But James’s family was good to her, and she worked hard in every successive business venture that they would begin, and fail, and begin again. They were still poor, but with prospects.

The first house was one room, cemented with dung and mud mortar. There was one night when the rain had been relentless, and the house began to flood. She'd sought refuge on the little bed with her first baby, while the rising water floated centipedes below. It was pitch black, and the dark water must have looked like an oily galaxy, undulating in the haze of blue moonlight.

“I thought to myself— Lord… what I get myself into here?”

Eventually, she’d genesis a garden from the mud around the house. She’d line the unpainted banister with flower pots until it was beautiful. James had kept his part in the bargain, he was a businessman to the core.

All I ever wanted was to have a nice home, with a pretty flower garden. My dream was to be a home-maker, taking care of my children. I did not reckon with my risk-taking adventurous husband, a man who enjoyed making quick decisions and telling me when the deed was done. Some of his ventures succeeded, others failed, but he never gave up. We began with a shop and a restaurant, both of which folded up.

- Cecelia

As soon as things would begin to go well, James would get an offer he could not refuse.

"You don't sell a failing business," he would say.

The same thing happened to this first house. Now that it had been made so attractive, he sold it, and once again they found themselves moving. Sasa would come to live with them in the new house.

“ It was another start,” she’d said.

.04

SILLA

Meanwhile, back in Poole, Silla was coming of age, and she had questions.

After her mother’s death Silla had remained in her father’s care, an arrangement that had upset the natural order of things. When the mother dies, the child would usually go to live with the grandmother.

The average life span of a dog is twelve years, eight years longer than many of the babies born here. The odds were even worse for the babies born in Indian barracks. There, a woman might have ten children, and see only four of them live to speak their own names. The odds in Poole are a little better, but not by much. Colonial power was distant, and everywhere, and largely indifferent to the death callers who would walk the streets with a bell, calling out the name of the person who had died. There were no phones then, and the callers would have to let the neighborhood know that one among them was to be buried, one among them was grieving, one among them was perhaps available again to be married, to be with new child, or to be fatherless, or motherless forever. The carpenters would have to know when to build a box, and approximately how big, and the diggers would have to know whether they might be needed in the churchyard in the morning. This was a time still drawing slowly past, led by horse carts. Large wheeled carts taking the dead to be buried, followed by long processions of everyone you might know in your life, chanting and singing hymns.

Her mother’s name had been called in the streets: Georgie. Upon hearing the story of her death, Silla knew only one thing for sure — she didn’t want to live the life of scarcity that her mother and father had lived in this place. She was sixteen years old. She would go to live with Cecelia, James and Sasa.

“Silla. Born 1925.”

It was 1942. Silla had liberated herself from her father’s house during wartime.

The presence of these strange white men in sailor suits threatened to unmoor politesse. Quite unlike the French Creole, and British white men, who would only proposition brown women far from the eyes of their mothers, wives and societies, these Yankees would entreaty them on the streets. Women were losing their chastity left and right. These were perilous times to be a young lady . One had to be careful, your body could be taken from you — inveigled away, or snatched. And in this era, your chastity was your price.

Silla and I used to go for walks in the evening time, enjoying our chats. One day, some Yankee soldiers from the base started to follow us. Obviously they thought we were available. Well! We walked back home as fast as we could, and when we got there, James had to make sure we were locked inside the house. It was a reminder that we were still in war days.

- Cecelia

In the rural areas. and in the cities, local men suddenly found themselves with unwelcome competition for their wives’ attention. Brothels were surfacing in record numbers across the capital, and calypsonians were singings songs about ‘fallen women’.

“San Fernando.”

Silla went out in search of work. Her world had opened up. It was still not the capital, but this new town even had a post office. Her sister Merle remained in Poole with its unpaved roads, but here in San Fernando, Silla walked on asphalt streets. There was electricity. Any farmers found here, came only in the mornings to sell their goods, and left by the afternoon.

“Silla with Cecelia’s first daughter, Mary.”

Silla felt at home in her new job, and had settled into the rhythm of life with Cecelia and her growing family. But the first job Silla had found after leaving Poole, had been a difficult beginning. She’d worked in a shop run by a Jewish man, whose religion would have made him ineligible to receive the full merits endowed to Christian white men. Silla had been living in a larger town for the first time. It had been more ethnically and economically diverse than she would have encountered in Poole. She would have to acclimate to her inconstant, and sometimes infelicitous social position in the milieu.

The leaden imputations of class, and of color, made it so she could not so easily move into the good esteem of those with better social ascendancy. Even though she'd been camouflaged by the markers of better class - the new outfits, the grooming - this white man had located her easily, and had put her back where she belonged.

The thing you have to remember is this: In the eyes of this white man, she was a sum totaling nothing. She could be called anything, told anything by a white man. Admired from below, yes, but dismissed from above. This was not a subjective judgment. It was written legibly on the social document, the contract that they all lived by. This man, who sixty years later still inspired her contempt, knew that she could be considered nothing, and the fact that she disagreed did not matter at all. In his company, her relative lightness and good hair were revealed to be a paper crown.

Silla’s dresses, their fabrics carefully laundered, their seams carefully sewn, and carefully pressed, were tailored to trap dignity. They contained within them the urgent and innate need to be seen in the fullness of her humanity. And this desire, the British did not invent. They had contrived the hegemony wherein blackness was debased, and whiteness, signaled through a facility with British mores, had been elevated to the status of religion. Its preeminence over other cultural forms had become tenants of faith. It was the god that Creole people had been given, and they were acolytes of its rituals. This performance of respectability was the smoke of incense, but the will to burn it was their own — it was primal, it was indigenous. To be denied the recognition of your connate dignity, was to be erased. Silla wore respectability as a cloak of visibility. She wanted them to see that within her lived the divinity that consecrated whiteness. She had sewn these dresses to contain god.

But she would be denied, because in the colony, in the 1930s, she was quite simply ‘less’. Casually ‘less’ in a mundane and sober sort of way, the way the sky is prima facie above you; a prosaic truth; inevitable as gravity; so obvious that it's not worth mentioning. It was fate, and fate is not afraid of you. Fate doesn’t even know your name. This was the reality that she and Cecelia had been born to. This was the factory that made my grandmother’s wisdoms.

.o5

The Story of the Silla’s Wedding

Silla had changed jobs again. This time she’d gone to work in a store she called the ‘The Indian Shop’. So called because it catered to the nearby Indian laborers who worked that land. Their lot at this time was arguably worse than that of a black man. A black woman in the capital might pay an Indian man a half penny in the market, to carry her goods on his head, while walking paces behind her. The Hindus especially, had been locked out of education altogether from the very first man. The planter class would not make the same mistake they had made with the black workers, or the Chinese indentures who'd escaped almost as soon as they'd arrived. The Indians brought here under indenture were long accustomed to unyielding poverty, as most would have come from the lowest castes in India. Their barrack yards were more like pens than houses. No running water, no hygiene to keep their babies alive. In Sasa’s time, they would have been shunned by the blackest negro. And by the time Silla went to work in the Indian shop, the men who would come to buy, and drink penny rum outside, were still tied to the land.

There was a bus that would bring boys to the town where Silla worked in the shop.

These would have been the professional class of boys.

In the complex social ecosystem of the 1930s, people could be sorted both by skin color, and by class - the rural poor and black on one end of that spectrum, and the light-skinned planter class of French Creoles on the other; those who worked the land, and those with a history of wealth in the plantocracy. But in the spaces in-between, people navigated nuanced metrics of skin tone, education and employment. A brown or black person with an education, and a white color job, could find themselves occupying an enviable status. These were the Civil Servants, the emerging middle class who often shunned their agricultural roots, and its demoting connotations. The brown and black educated middle class could recite Oberon’s soliloquy in a Midsummer’s Night Dream from memory; they could trace the origin of any word back to its Latin roots, all while walking the length of a room with a heavy book poised on their heads. Such was the training in the high schools at the time. And when they would find social avenues blocked to their particular complexion, as they inevitably would, they would take solace in the idea that they'd conjured the phantasmagoria of British gentility better that the White British, or French Creoles themselves. Blocked from entering the world of commerce, parents focused all their ambitions on the professions: law, medicine and the civil branches of government, salaried with the signature of the King himself. Their resources were poured into educating their children. These boys and girls would go to extra lessons in the morning, again in the evening, and return home to do their homework under the close, and strict attention of their parents. One could never fully overcome the handicap of skin color, but you could put distance between yourself and blackness. Education was all, it was self-respect in defiance of the fact that they were blocked from attaining the full recognition of their respectability. You could never become white, but you could achieve whiteness. The country clubs were still whites only, as were many of the positions of authority. But while planter class was preoccupied with lineage and legacy, the middle class was preoccupied with the future. They embraced the values of hard work, decorum and discipline. But it was also this middle class, feeling the stigma of an agrarian past at their heels, who were often as eager, if not more so, than the whites to look down on the black, and brown people, from the rural areas. As the saying went, a person could move from the drawing room back into the kitchen by marrying down, either through class, or through color. Needless to say then, the view from the kitchen framed these young men and women as beau ideal.

“Civil Servants. 1945.”

It was this particular kind of boy who had begun to notice Silla.

In the hierarchy of beauty, Silla could not imagine herself above a light-skinned Syrian girl. She found it hard to believe, that he might have chosen to look at her, over the other girl’s nice, long hair. And although this boy was also brown, because he was on course to enter the middle class, he could have done better than a brown shop girl.

But she’d started to hear from people in town, that this boy was asking question about her. It was clear that her friend in the shop had been right, he had chosen her.

Not long after he’d started visiting the house, James had again decided to sell his business. They moved to another town to try their hand at a new venture. Silla moved with them, and around the same time the boy was transferred to a new post.

Jean was my grandmother’s forth child.

One day, during their courtship, the boy had waited for her outside her church. During the mass, someone had whispered in her ear that there was a young man out there who wanted to speak with her. She'd waited until the mass was over, and then had gone outside to discover that it was him standing there in the churchyard.

"I want to show you where I live," he'd said.

And Silla had been vastly unsure that going with him would be a good idea. Cecelia would have been expecting her back at the house at a certain time. But she'd said,

"Allright," and they'd set off walking.

They walked until the road turned into a narrow trace that cut through reclaimed swampland. The landscape was sparsely adorned with houses. It was a nascent community, called into being by the aspirations of growing numbers of black and brown people who had secured some small measure of social mobility for themselves.

They stopped in front of a small house.

"Whose house is this?" she'd asked him.

It was his, he'd said, and he had bought it with a government loan. A local bank had been started by a Chinese man. It was the first bank that would grant loans to black, and brown people at the time. The boy had lived there with his mother.

When Silla would return home later that afternoon, still in her church clothes, she would say to Cecelia,

"You know, Cece, this boy took me to see his house today. It's his house, he said. He bought with a loan."

“Silla and Rupert Rosales. 1949.”

The flower girls are Cecelia's daughters: Mary, Lynn and Annette.

This boy was also 'good brown'. His mother might have forgiven Silla's poverty, had she been of a better color. When it came to brides, many other ‘good brown’, middle class parents, would have made similar calculations. At least then, there would have been some quantitative advantage to this union. She wanted for her son, what Sasa had wanted for Cecelia. But Silla offered no advantage. Her better color, was not better enough here, and so once again, Silla found herself reduced to a sum of nothing.

They went on a weeklong honeymoon to the beach. Cecelia had rented a house for the new couple.

“That was the most unhappiest week I spent my life.”

She moved into the little house bought with a loan, and found herself very much alone in this neighborhood of civil servants and their wives. She was a brown girl made black, darkened by her relative poverty, and lack of education. Her new mother-in-law was determined not to let her forget it. Instead of moving out, she'd stayed, and now lived with the new couple. Silla had stopped working, and so she was pregnant without a penny of her own.

“Vendors.”

She would spend her days absent from the house, seeking refuge with Cecelia and her family. After a while, her husband started to worry.

The mother-in-law claimed that the house in fact belonged to her, and continued to treat Silla, and the marriage as trespass.

"You dream all your life of owning a house, you growing with this thing in you," Silla had said, but daily indignities made this new life feel mortgaged.

Silla had gone to the capital. Port of Spain, would have been a universe away from her familiar. People from all over the world would have been here, chasing ambitions alien to Silla. Native sons and daughters were returning with their educations from abroad, and the city was growing restless under the weight of Empire. Inchoate trade unions were negotiating their existence. CLR James’s missives had been read on the island, and his former pupils had begun to quietly contemplate, but not yet articulate the meaning of nation. In two years they would be reading Fanon. This was the seat of power, the right place for Silla to go looking for an authority that could be borrowed in her predicament.

Silla would never have had cause to visit a lawyer before. Never before would Silla have had cause to visit a bank. Before this marriage, she worked for a weeks wage at a time - no need for a bank. Cecelia had opened her a bank account in her name, so that she could buy provisions. Silla would have heard of loans in conversation, but the magistracy that made them inviolable, the polity that gave this lawyer his authority, were anonymous and unfamiliar, no relation to her family of circumstances. She had met civil authority before in the form of police, but those were men with names.

Assured now, that she had the law on her side, she sought next to convince God. She began making pilgrimages to the convents and monasteries.

The mother-in-law had finally left them in peace, at least for now, at least on weekdays. And Mrs. Silla Rosales began to remodel the house in her own image. She put flower pots on the banister as Cecelia had done all those years ago. But her baby had been born sick. A result, she was sure, of all the stress she had been under during her pregnancy. She and her husband Rupert, would go on to have three other children. But that first boy would die at age thirty three. The doctors said it was a brain tumor, but Silla knew the real reason.

“Silla’s children.”

.06

The Chow Family

By the time I came along my family was middle class. We were the Chows. My grandfather’s enthusiasm for endeavors, and his willingness to take risks, paired with my grandmother’s constancy and practicality, had lifted us up in a generation. My grandmother’s devotion to education had sent all eight of her children to high school, and later to colleges as far away as England. Even the daughters, whom my Chinese Grandfather did not at first think would warrant the same schooling as the two boys, had been sent. My grandmother had insisted. She had even taken all of them to the same good angel, Mr. Mitchell, for extra lessons.

Silla had followed her lead, and educated her children as well. Sending them to colleges in places as far away as Canada and America. Their children had become lawyers, teachers, leaders in business, and there was even a nun.

“The Sisters.”

I grew up in the same house in Sangre Grande that my mother had lived in as a child. Cocoa, coffee, and nutmeg was my grandfather’s business then. We had land in the mountains, and the crop would be brought down to be sorted into bags for shipment abroad. He was an estate man of sorts now himself, and my grandmother managed the accounts. On our property, there was an old nutmeg house, operating the way it had since the eighteenth century. There was Mr. Ali of the long limbs, and surprising strength. Every morning he would spit on the bottoms of his bare feet for traction, and push open the leaden roof that rested on wheeled tracks. The colossus would open with a yawn, exposing the dunes of nutmegs to the sun.

I remember the sound of that nutmeg house, the music of women’s chatter as they sat on the floor sorting the red mace, skirts tucked inside crossed legs, the cracking of nutmeg shells, and the dust that hung in shafts of light, making that old plantation style warehouse, with its pitched roof, look like a cathedral. The fragrance of nutmeg would stay on my skin, and scent my hair. How many women had smelled like this for hundreds of years?

When schools were closed for the holidays, the women who worked in the nutmeg house, would bring their children with them. Black boys and girls running loose on our land, and I indistinguishable from them. My eyes were not as trained as Silla’s and my Grandmother’s would have been by that age, to see the subtle, and diverging prospects in our gradations of complexion. It was about to not matter as much in our futures, as it had mattered to theirs. But of course, it would still matter, and had already mattered.

There was a simple thing that had happened once. I was a teenager on the beach with friends.

“I’d better go in the shade now, I don't want to get too dark.”

I had said it. This casual and unexamined thought. There it was - The disrelish for my own body, the scorn for my own face, seeded in me generations ago, had blossomed in puberty. I knew, like geese flying north in formation know, like crabs releasing their eggs to the sea only under full moon know, I knew to be vigilant of how my skin would betray me in the sun.

I might never even have remembered this moment — so mindless and unextraordinary was the thought — were it not for the unforgivable fact that the friend I’d said this to, had been so much darker than I. She’d heard it, both the loud message and the cruel quiet one. And she’d felt it.

Every time I remember this incident I clench with shame. How oblivious, how callous, how terrible. And how tragic too, that we so insidiously come to feel proud of our lighter skin color, like a dog who grows to love the master that keeps him chained in the yard. No one would question this fidelity, after all it is in a dog’s nature to love the hand that feeds him. What the master gives us, we do need - Who can live without some little bit of affection? Who can live without food? But oh, how voraciously we hoard those scraps that we are given. How taut the chain as we strain to meet him. He does not look at us but for a moment. But oh, how we ache for those moments when we are anthropomorphized, and made precious by the gaze.

Did a man bestowed from birth with status of lightness, spend this much time pondering the intricacies of dignity?

Sitting between knees, having my hair combed, I used to feel hurt, thinking that I could only ever be so precious, could only ever be a portion of beautiful. I thought that’s what you’d meant with those wisdoms.

But hearing this story, perhaps now I can finally be hurt for the right reasons. We were not adversaries after all, Granda. I am not at war with you. We were inside a war together. Hemmed in by bigger things, powerful things, that’s what you’d meant. That was the warning. I look up, and finally see the battlefield strewn for generations behind me with bodies just like mine. The children of Eve.

But the world is different enough. The debt has been paid. And you don’t have to worry about me anymore. I am free, enough.

Free to marry whomever I want, for sentimental reasons. Free to wear my hair as I want, and suffer derision, perhaps, but not destitution. To dare to think myself as beautiful as anyone lighter than me, to sometimes forget, and free to remember again.

Free to forgive myself for being black.

Now I am in a different colony - America. And its history tries to ensnare me inside different boundaries. But as I remember past my one little life, I am rendered enormous through knowing myself beyond this individual body. I remember past today, back through all the days, five generations of days. We have already been told too many things and believed them. So, if new histories conspire to ensnare me, well, I will go out the back way. I intend to roam.